105 groups comment on the role of PBMs on patient access and affordability of prescription drugs

Chair

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, D.C. 20580

Dear Chair Khan:

We, the undersigned 105 organizations, on behalf of millions of patients and Americans who live with complex conditions such as HIV, autoimmune diseases, cancer, diabetes, kidney disease, lupus, hemophilia, mental illness, and hepatitis write in response to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) request for public comment on the impact of pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) practices on consumers. Specifically, we offer comments on how PBMs impact the health and well-being of patients who receive their health coverage through the private insurance market. While most people think insurers make the majority of decisions regarding health coverage and affordability, when it comes to prescription drugs, it is the PBMs that drive much of the decisions as to what medications a beneficiary can access and how much they pay for them. We commend the FTC for its leadership to investigate the impact that PBM practices have on the patient communities we serve and believe this represents a critical step forward to improving patient access and affordability to necessary medications.

While originally intended to process pharmacy claims, PBMs have evolved into one of the largest drivers of determining prescription drug access and affordability. As we discuss in more detail below, in the private insurance market, PBMs control which drugs are on plan formularies, utilization management such as step-therapy and prior authorizations, what tier each drug is on along with several other cost-sharing decisions, and pharmacy access. All of these actions are carried out with little transparency and regulation.

Today, the power and influence of PBMs have grown in that three companies now are responsible for processing about 80 percent of all prescription drug transactions and these same three PBMs are all integrated through ownership with three of the larger insurers in the country.[1]

This concentration of power provides them with an overly sized role in deciding what drugs patients can take and at what cost. Often this interferes with the decisions of medical providers and, due to high patient cost-sharing, makes prescription drugs unaffordable for many patients. This not only impacts the health of the patients we represent but the health of the entire country and healthcare spending in other areas if patients are not able to access and afford the medications that their providers prescribe.

Below is how PBMs directly impact patient access and affordability of prescription drugs in the private insurance market.

Formulary Decisions

PBMs determine what drugs are on a plan’s formulary for the insurers or employers that contract with them, and therefore, determine what drugs a patient can take. They also decide when to add newly approved FDA drugs and, at times, remove drugs from a formulary. While these decisions should be based on clinical guidelines and medical necessity decided by experts on a Pharmaceutical and Therapeutic (P&T) Committee, PBMs also make decisions on the amount of rebates that they negotiate with drug manufacturers. Therefore, a drug’s inclusion or removal is frequently determined by the amount that a manufacturer offers a PBM in the form of rebates and not solely on clinical guidelines and the best interest of patients. To make matters worse, PBMs sometimes remove drugs from a formulary mid-year and patients who are on a stable regimen are forced to switch to an alternative medication for non-medical reasons.

Over the years, there has been a growth in the number of outright drug exclusions from plan formularies that the three largest PBMs offer to their clients. According to an analysis by Drug Channels, these three PBMs in 2022 exclude on their national formularies between a low of 433 and a high of 492 drugs.[2] Just having such a national formulary that the PBMs offer their clients gives them a great deal of power and pressure over drug manufacturers and allows them to extract larger rebates.

Utilization Management

Once a drug is on a formulary and a provider prescribes it, it does not automatically translate into the patient having the ability to access the drug. PBMs also are responsible for implementing utilization management techniques such as prior authorization and step therapy. Prior authorization requires a patient to meet certain established conditions or circumstances before they can qualify to take a certain drug that the provider must submit and certify for approval. Step therapy requires that a drug fails for a patient before they can access the drug prescribed by the provider. While some of these utilization management techniques are based on clinical guidelines, many of these decisions, again, are the result of rebates extracted by the PBMs. A higher rebate paid to the PBM may lead to less restrictive utilization management on a drug, and vice versa, lower rebates can lead to more restrictions.

An analysis conducted by Avalere of employer and exchange plans use of utilization for brand name drugs in 2020 found that over 50 percent of the drugs in certain therapeutic classes of drugs were subject to utilization management. For example, drugs treating depression, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis all had over 50 percent of their drugs subject to utilization management.[3] The trend of utilization management is growing. Over the years 2014 to 2020 the use of step therapy in the commercial market grew 546 percent for HIV drugs, 478 percent for cardiovascular drugs, and 220 percent for multiple sclerosis drugs. Over the same years, the growth of utilization management in commercial plans grew by 478 percent for cardiovascular drugs and 309 percent for multiple myeloma drugs.[4]

Patient Cost-sharing

PBMs have a major influence on how much patients pay for their medications. The amount people pay for their prescription drugs is determined by a number of factors, including plan benefit design, such as the use of co-insurance and high deductibles; drug tiering; and whether copay assistance counts towards a patient’s deductible and out-of-pocket maximum. PBMs have a primary role in each of these issues, along with the level of rebates and other costs in the drug delivery system as cost-sharing is based on the list price of the drug and not on the net price of the drug negotiated by the PBMs. Before examining each of these concepts, the extent of patient cost-sharing must first be put in context.

- According to a review of CMS’ National Health Expenditures Accounts data, in 2019 individuals were responsible for paying 14.5 percent of the total cost of prescription drugs. However, for hospital care, which accounts for more than three times more of the total spending, patients were responsible for paying only 3 percent. Despite the smaller total amount of spending for prescription drugs, the total out-of-pocket spending for prescription drugs was actually higher than all the out-of-pocket spending for hospitals.

- Out-of-pocket costs for non-retail medicines, according to an IQVIA analysis, reached $16 billion in 2020, up from $13 billion in 2015.

- That same study found that when out-of-pocket costs reach $75-$125, 31 percent of patients abandoned their brand name prescriptions at the counter; when those costs hit $250, that number rises to more than 56 percent of patients.

- In 2020, patients starting a new therapy abandoned 55 million prescriptions at pharmacies.

- According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, average deductibles for covered workers increased 212 percent from 2008 to 2018. About 40 percent of beneficiaries with employer-sponsored coverage have a high-deductible plan with deductibles exceeding $1,500 for 20 percent of those beneficiaries.

- For qualified health plans, CMS reports that the median annual deductible for an individual on a Silver plan in 2022 is $5,115, which is an increase of 23 percent from 2018.

- According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the average payments towards coinsurance rose 67 percent from 2006 to 2016.

- A recent study based on Federal Reserve data found that most households do not have enough liquid assets to meet the typical out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage of $4,272 in 2021.

- A review of federally funded exchange and California plans found that for Specialty Tier drugs, 93 percent of the plans use co-insurance with an average of 44 percent.[5]

- According to an IQVIA analysis of brand medicines across seven therapeutic areas, anywhere from 44-95 percent of patients’ total out-of-pocket spending for brand medicines in 2019 was due to deductibles; and for oncology and multiple sclerosis, deductibles and coinsurance accounted for more than 90 percent of total patient out-of-pocket costs.

Impact and Magnitude of Rebates

In this comment letter, the impact of rebates on drug formulary and utilization management have already been discussed. Rebates also play a significant role in determining patient cost-sharing since as the beneficiary meets their deductible, they are paying on the list price, rather than the net price of the drug. The same is true when patients are forced to pay for their drug using co-insurance, which is a percent of the list price of the drug. As noted above, both deductibles and the use of co-insurance are increasing.

It is estimated that in 2020 just over 50 percent of drug expenditures were realized by entities other than the drug manufacturers. While some of these expenditures along the drug supply chain were statutory payments, such as Medicaid and 340B rebates, over $102 billion or 20 percent of total brand name drug spending was associated with negotiated health plan and PBM rebates and fees. In 2018, these rebates totaled $82 billion, demonstrating that they are rapidly increasing.[6]

After the State of Texas passed a PBM transparency and reporting law, they found that in 2019 PBMs received $858 million from drug manufacturers. Only $16 million (less than 2 percent) was passed on to enrollees, $178 million (21 percent) was retained by PBMs as revenue, and $664 million was passed on to health issuers.[7]

As this data demonstrates, a very small amount of the rebates is being shared with the patients who are responsible for generating them. Not only are beneficiaries who use prescription drugs paying their cost-sharing on inflated prices, but they are also generating revenues for PBMs and insurers to benefit all beneficiaries since some of those revenues are used to reduce premiums.

Plan Benefit Design

Many PBMs work with insurers and employers to determine plan benefit design. This includes the size of the deductible and whether prescription drugs are within or outside the deductible, along with the use of copays or co-insurance and the amount of each. As noted above, there is an increased use of higher deductible plans and co-insurance.

Since prescription drugs are critically important for people with chronic conditions, many of them just take them throughout the year and need them to remain healthy and alive. In the past, prescription drugs were outside the deductible or separate from the medical deductible. However, an analysis conducted by Milliman that compared drug benefits in silver plans and employer-sponsored coverage found that a major difference is the greater use of a combined deductible for medical and drug spending in silver plans. Therefore, people in silver plans are paying a greater share of their total drug spending.[8]

Drug Tiering

PBMs are also responsible for determining the tier each drug is placed on, which determines the level of corresponding patient cost-sharing. As more drugs are placed on higher tiers, more patients are responsible for paying for them. While most plans utilize four tiers, 27 percent of the federally funded exchange plans now use 5-7 tiers.[9] The use of more tiers also translates into higher cost-sharing. Like other formulary decisions, PBMs do not base their decisions on clinical appropriateness or list price alone but use rebate negotiation to determine drug tier placement. PBMs negotiate with drug manufacturers on tier placement. For example, in return for a higher rebate, the PBM will provide a certain drug lower tier placement and vice versa.

PBMs have also created a tier for “specialty drugs,” which comes with corresponding high cost-sharing. Originally used for drugs that require special handling, they now seem to apply to all drugs over a certain price point. Some PBMs place all or a majority of drugs to treat a certain condition or disease on the highest drug tier, such as a specialty tier. The federal government has called this practice “adverse tiering.” As part of implementing the nondiscrimination provisions of the Affordable Care Act, which state that you cannot discriminate against beneficiaries based on their health condition and design insurance benefits that discriminate against people based on their health needs, the federal government has stated that this practice is discriminatory.

In the recent proposed Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters rule, CMS advised that “instances of adverse tiering are presumptively discriminatory and that issuers and PBMs assigning tiers to drugs should weigh the cost of drugs on their formulary with clinical guidelines for any such drugs used to treat high-cost chronic health conditions to avoid tiering such drugs in a manner that would discriminate based on an individual’s present or predicted disability or other health conditions in a manner prohibited by § 156.125(a).” [the rule that describes discrimination]

Unfortunately, we find numerous instances in which PBMs continue to place all or almost all drugs on the highest tier, which not only leads to higher patient cost-sharing but is also discriminatory.

Treatment of Copay Assistance

Due to the proliferation of high deductibles and high-cost sharing expressed in terms of co-insurance, for patients to afford their prescription drugs, they have had to rely on manufacturer copay assistance. According to IQVIA, the total amount of copay assistance reached $14 billion in 2020. Of commercially insured patients on branded medications, 14 percent of them used copay assistance to reduce their out-of-pocket costs in 2020.

However, more and more insurers and PBMs have instituted harmful policies that do not apply copay assistance towards beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs and deductibles. These policies are often referred to as “copay accumulator adjustment programs.” This violates existing regulations that define “cost sharing” as “any expenditure required by or on behalf of an enrollee with respect to essential health benefits; such term includes deductibles, coinsurance, copayments, or similar charges, but excludes premiums, balance billing amounts for non-network providers, and spending for non-covered services.” 45 CFR 155.20 (emphasis added).

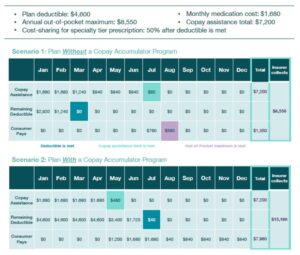

Because of the integration of PBMs and insurers, they are able to more closely track all parts of the pharmacy transaction process and implement these policies that significantly increase out-of-pocket costs for patients. It also allows insurers, with the help of their PBMs, to “double dip” and increase their revenue by receiving patient copayments twice. Consider the following two patient scenarios developed by The AIDS Institute.[10] In both scenarios the patient receives copay assistance to afford their drugs; however, in one the copay assistance counts towards the beneficiary’s cost-sharing obligations while in the other it does not since the patient’s insurer and its PBM have instituted a copay accumulator adjustment policy.

In the scenario when the copay assistance counts, the beneficiary pays $1,350 annually, and the insurer collects $8,550. However, when the copay assistance does not count, the beneficiary ends up paying $7,960 annually and the insurer collects almost twice as much at $15,160.

To make matters worse, issuers continue to conceal these policies deep in plan documents and leave patients unaware of the increase in patient costs that they might be subject to.

Unfortunately, the use of these policies is growing. In the 2021 annual survey of employer plans with more than 500 members, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 18 percent of all employers have instituted such policies.[11]

A recent study highlighted the negative impact of copay accumulator programs, finding that patients who are subject to the programs fill prescriptions 1.5 times less than patients in high deductible health plans. Additionally, patients subject to these programs experience a 13 percent drop in persistence between months 3 and 4 as they reach the cap in their annual benefits and terminate their therapies.

Non-Essential Health Benefits Drugs

Another scheme that PBMs are implementing is to designate certain higher priced “specialty” medicines as “non-essential” and then raise the cost-sharing to ensure that they collect all of the patient assistance offered by the manufacturer but do not count it towards the beneficiary’s cost-sharing obligation. Under this arrangement, the plans often collect payments far exceeding the out-of-pocket maximum. If the beneficiary does not participate in this scheme, they are forced to pay higher cost-sharing and it will not count towards their out-of-pocket maximum.

Pharmacy Access

PBMs are also responsible for determining how and where patients receive their medications. Insurers contract with PBMs that require their beneficiaries to use a specific mail order or pharmacy network. If the beneficiary is allowed to pick up their drug elsewhere, they would be subject to higher costs. While the use of mail order pharmacies may be beneficial for many people, some people prefer to pick up their prescriptions from a local pharmacy to personally discuss their medications and seek advice from a pharmacist. Others do not want their drugs delivered to their house out of confidentiality concerns or because they lack a permanent address. People may want to use the pharmacy of their choice, which could be the one that is closest to their residence or place of employment, instead of traveling far to the one that their PBM requires them to use. This is especially important in rural areas of the country where there is not a wide choice.

As described above, PBMs play a large part in how patients access and afford their prescription medications. We call on the FTC to use all the power within its purview to help alleviate these harmful policies and practices that make access to prescription drugs out of reach for patients and impact the health of our nation. At a time when American consumers are struggling to afford and access their treatments and other basic necessities like groceries, gas, and rent, we hope that the FTC will take clear action to more effectively regulate how PBMs operate within the health care system.

Should you have any questions or comments, please contact Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute at cschmid@hivhep.org, and Quardricos Driskell, vice president of Public Policy and Government Affairs of the Autoimmune Association at quardricos@autoimmune.org.

Sincerely,

Accessia Health

ADAP Advocacy Association

ADAP Educational Initiative

Advocacy & Awareness for Immune Disorders Association (AAIDA)

Advocacy House Services, Inc.

AIDS Alabama

AIDS United

Aimed Alliance

Allergy & Asthma Network

Alliance for Aging Research

Alliance for Patient Access

American Behcet’s Disease Association

American Kidney Fund

American Liver Foundation

Association of Nurses in AIDS Care

Autistic Self Advocacy Network

Autoimmune Association

Bienestar Human Services

Black AIDS Institute

Brain Injury Association of America

California Chronic Care Coalition

California Chronic Policy Alliance

California Hepatitis C Task Force

CancerCare

Caregiver Action Network

Caring Ambassadors Program

Celiac Disease Foundation

Chronic Care Policy Alliance

Chronic Disease Coalition

Coalition of Skin Diseases

Community Access National Network (CANN)

Community Liver Alliance

Conquer Myasthenia Gravis

Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation

Dermatology Nurses Association

Diabetes Leadership Council

Dysautonomia International

Exon 20 Group

Georgia AIDS Coalition

Global Healthy Living Foundation

Global Liver Institute

Good Days

Hawaii Health & Harm Reduction Center

HealthHIV

Healthy Men Inc.

HealthyWomen

Hemophilia Association of the Capital Area

Hep B United

Hep Free Hawaii

Hepatitis B Foundation

Hepatitis C Mentor & Support Group—HCMSG

HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute

ICAN, International Cancer Advocacy Network

Immune Deficiency Foundation

Infusion Access Foundation (IAF)

International Foundation for AiArthritis

International Pemphigus Pemphigoid Foundation

Legacy Community Health

Looms for Lupus

Lupus and Allied Diseases Association, Inc.

Lupus Foundation of America

Men’s Health Network

MLD Foundation

Multiple Sclerosis Association of America

Multiple Sclerosis Foundation

National Blood Clot Alliance

National Consumers League

National Grange

National Health Law Program

National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (NVHR)

Neuropathy Action Foundation (NAF)

Oregon Rheumatology Alliance

Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease

Patient Access Network (PAN) Foundation

Patients Rising Now

Pharmacists United for Truth and Transparency

PlusInc

Prism Health North Texas

Pulmonary Hypertension Association

RetireSafe

Rheumatology Nurses Society

SisterLove, Inc.

Spondylitis Association of America

Susan G. Komen

The diaTribe Foundation

The National Adrenal Diseases Foundation (NADF)

The US Hereditary Angioedema Association

The Wall Las Memorias

Thrive Alabama

Touro University of California

Transplant Recipients International Organization (TRIO)

Triage Cancer

U.S. Pain Foundation

United for Charitable Assistance

Utah AIDS Foundation

Vasculitis Foundation

Virginia Breast Cancer Foundation

Virginia Hemophilia Foundation

Vitiligo Support International

Vivent Health

wAIHA Warriors

Whistleblowers of America

Whitman-Walker Health

Whitman-Walker Institute

[1] Dr. Adam J. Fein, “The Top Pharmacy Benefit Managers of 2021: The Big Get Even Bigger,” Drug Channels, April 5, 2022, https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/04/the-top-pharmacy-benefit-managers-of.html.

[2] Dr. Adam J. Fein, “Five Takeaways from the Big Three PBMs’ 2022 Formulary Exclusions,” January 19, 2022, Drug Channels, https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/01/five-takeaways-from-big-three-pbms-2022.html.

[3] Tiernan Meyer, Rebecca Yip, Yonatan Mengesha, Damali Santiesteban, Richard Hamilton, “Utilization Management Trends in the Commercial Market, 2014–2020,” Avalere Health, November 14, 2021, https://avalere.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/UM-Trends-in-the-Commercial-Market.pdf.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Avalere PlanScape®, a proprietary analysis of exchange plan features, December 2021.

[6] Andrew Brownlee and Jordan Watson, “The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain, 2013-2020,” BRG, January 7, 2022, https://www.thinkbrg.com/insights/publications/pharmaceutical-supply-chain-2013-2020/.

[7] “Prescription Drug Cost Transparency, Pharmacy Benefit Managers,” https://www.tdi.texas.gov/reports/documents/drug-price-transparency-PBMs.pdf.

[8] Kenneth E. Thorpe, Lindsay Allen, and Peter Joski, “Out of Pocket Prescription Costs Under a Typical Silver Plan Are Twice as High as They Are in the Average Employer Plan,” Health Affairs 34, no. 10 (October 15, 2015), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0323.

[9] Avalere Health, Analysis of Formulary Tiers in FFE Plans Compared to State Exchanges with Standardized Plans, October 2020.

[10] The AIDS Institute, “Copay Accumulators and Insurance Issues,” February 1, 2022, https://aidsinstitute.net/protecting-patients-and-removing-barriers-to-care/copay-accumulators-and-insurance-issues#:~:text=Report%20Reveals%20Prevalence%20of%20Hidden,(June%206%2C%202020).

[11] KFF, “Employer Health Benefit, Annual Survey, 2021,” https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2021-employer-health-benefits-survey/.