Comments on the 2026 NBPP proposed rule

Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

200 Independence Avenue, SW

Washington, DC 20201

RE: Comments on Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters for 2026 Proposed Rule [CMS-9888-P]

Dear Administrator Brooks-LaSure:

The HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute, a leading national HIV and hepatitis policy organization promoting quality and affordable healthcare for people living with or at risk of HIV, hepatitis, and other serious and chronic health conditions, is pleased to offer comments on the Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters for 2026 Proposed Rule (Proposed NBPP Rule).

On November 4, 2024, we submitted comments on the 2026 Draft Letter to Issuers, which can be found here. In those comments, we reiterate our profound disappointment with CCIIO and state regulators for not enforcing the strong ACA nondiscrimination patient protections, including a prohibition on adverse tiering in drug formularies and the requirement to cover the drugs included in widely accepted national treatment guidelines. We also outline a number of recent examples by insurers that CCIIO and state insurance regulators are permitting to operate that discriminate against people living with HIV by using benefit designs that discourage their enrollment.

While we appreciate the many steps that you are taking to make healthcare more accessible and affordable for beneficiaries, the majority of this comment on the Proposed NBPP Rule focuses on the need for CMS and related federal agencies to take the necessary steps to increase access and affordability of prescription drugs that should have been included in the Draft NBPP Rule but were not.

Risk Adjustment for PrEP & Hepatitis C

Before we address these issues, we want to voice our strong support for the proposal to include PrEP in the risk adjustment model. The HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute has signed on to a community letter in support of the proposal that we hope will begin for the 2026 plan year. As CMS correctly noted in the proposed rule, use of PrEP is not fully reflected in the current risk adjustment model since PrEP users do not have an active health condition with a diagnosis code. However, recognizing that insurers must cover all forms of PrEP without cost-sharing, PrEP use should be adequately reflected in the risk adjustment model.

We also do not believe the use of low-cost generic PrEP should be included in the same factor as brand name PrEP. There is a substantial price difference between newer branded name and older generic forms of PrEP and insurers should not be rewarded at the same rate for both. Additionally, newer and more effective long-acting PrEP drugs, which will undoubtedly be more expensive than daily generic PrEP, will likely be the predominant form of PrEP in the future. Therefore, we support excluding generic PrEP from the Affiliated Cost Factor (ACF).

We also support the proposal to begin to phase out the market pricing adjustment to the plan liability associated with Hepatitis C drugs in the HHS risk adjustment models and start treating Hepatitis C drugs consistent with other drugs. CMS rightfully concluded that the expected costs of Hepatitis C drugs have declined for many years and have stagnated due to the introduction of new and generic drugs and will only rise alongside the expected cost of other specialty drugs. We believe the phase out should progress as quickly as possible.

The remainder of the comment letter will focus on the following three issues:

- It has been over a year since the District Court for D.C. in HIV and Hepatitis Policy Institute et al. v. HHS et al. struck down the section of the 2021 Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters rule that allowed issuers to decide if copay assistance can count or not, and that same Court clarified, at the government’s request, that the 2020 Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters rule is now in effect. Therefore, issuers must count copay assistance, in most instances, and not implement copay accumulators. Instead of upholding the court’s decision, CMS has ignored it and stated that it will issue a new rule regarding cost-sharing. Doing great harm to patients, the federal agencies have yet to issue that rule and did not include it in the Proposed NBPP Rule, but indicated it would do so in the future. We urge the federal government to uphold the Court’s decision, and, if a new rule is proposed, it must ensure that copay assistance count as cost-sharing.

- We are pleased that CMS codified in the 2025 NBPP Rule for the small group and individual markets the policy that prescription drugs covered in excess of the state’s benchmark plan are considered essential health benefits (EHB) and are therefore subject to EHB protections, including annual cost-sharing limits. The 2025 NBPP Rule indicated that the federal government intends to propose a rule to apply this regulation to large group and self-insured plans. We are disappointed that this proposal was not included in the draft 2026 NBPP rule and urge the departments to issue a rule in the very near future to close this loophole for all plans.

- Employers are teaming up with vendors that force beneficiaries that use certain medications to enroll in an alternative program, which is not insurance, in order to bypass ACA laws and regulations relative to patient cost-sharing limits and other patient protections. They then find alternative funding mechanisms, such as patient assistance programs or imported drugs, to pay for the drugs. If the patient does not comply, they will be left paying the full cost of the drug. The federal government must take steps to prohibit the use of alternative funding programs.

Copay Assistance & Definition of Cost-sharing

More than a year ago, on September 29, 2023, the District Court for D.C. in HIV and Hepatitis Policy Institute et al. v. HHS et al. struck down the section of the 2021 Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters rule that allowed issuers to decide if copay assistance can count or not (see Attachment 1). That same Court clarified, at the government’s request, that the 2020 Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters rule is now in effect (see Attachment 2). That means that issuers must count copay assistance in most instances and not implement copay accumulators.

The rule states:

“Notwithstanding any other provision of this section, and to the extent consistent with state law, amounts paid toward cost sharing using any form of direct support offered by drug manufacturers to enrollees to reduce or eliminate immediate out-of-pocket costs for specific prescription brand drugs that have an available and medically appropriate generic equivalent are not required to be counted toward the annual limitation on cost sharing (as defined in paragraph (a) of this section).” 45 C.F.R. § 156.130(h)(1)

As HHS explained in adopting the rule: “Where there is no generic equivalent available or medically appropriate,” manufacturer assistance “must be counted toward the annual limitation on cost sharing” (84 Fed. Reg. at 17,545).

Instead of complying with the Court’s ruling and issuing guidance to insurers of their legal obligation, CMS is ignoring it, and instead, said it would issue a new rule regarding cost-sharing. However, to date, that rule has yet to be proposed and, much to the disappointment of the patient community, was not included in the Draft NBPP Rule. The Draft NBPP Rule merely states:

“HHS and the Departments of Labor and Treasury intend to issue a future notice of proposed rulemaking [to] address the issues arising out of HIV and Hepatitis Policy Institute et al. v. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services et al., Civil Action No. 22-2604 (D.D.C. Sept. 29, 2023), namely, the applicability of drug manufacturer support to the annual limitation on cost sharing.”

Every day that this rule is delayed is another day that patients are forced to pay more for their prescription drugs while insurers and PBMs continue to pocket billions of dollars meant for patients who are struggling to afford their drugs.

Not only does this inaction increase the cost patients must pay for their drugs, it creates confusion in the states and instability in the prescription drug market.

While a new rule is not necessary, if one were to be issued, it must require copay assistance to count as cost-sharing. Since the federal government sided against patients and defended the insurers and PBMs in our litigation, we are very concerned about which direction the proposed rule may take. We cannot imagine how the government can rule differently. The Court concluded what patient groups have long maintained: copay accumulators increase patient costs, increase drug manufacturer payments, increase insurer revenues, and are not drug discounts.

Counting cost-sharing towards the out-of-pocket (OOP) maximum is consistent with Congressional intent of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and is consistent with the plain language of the statute itself.

Title 42 USC Section 18022 both establishes the out-of-pocket maximum and defines the “cost sharing” that must be counted towards that OOP. That section of the ACA unambiguously provides that the “cost sharing” required to be recognized includes “deductibles, coinsurance, copayments, or similar charges.”

The plain language meaning of the statute is clear, with no carve-out to its broad applicability. The source of the funds used to satisfy these amounts is irrelevant to the statutory mandate that they must be counted. Any such “charge” to a patient, regardless of the source of the funds then used to satisfy that “charge,” must be recognized for purposes of the OOP maximum. It does not matter if the source of the funds used to satisfy any of those “charges” is a parent, a sibling, a family friend, a charity, or a drug manufacturer sponsoring a copayment card. The statutory text, along with the structure and purpose of the statute, speak directly and decisively to the question. They must be counted.

We urge the agencies to adopt, by regulation, that reading of the statute, as it is the only reading of the term “cost sharing” that CMS can lawfully adopt.

Patient Stories

The HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute receives countless stories from patients and their families who have been victims of copay accumulator policies forced upon them, usually without their knowledge, by their insurer and PBMs. They read press coverage of our court victory and wonder, if we won the lawsuit, why isn’t the copay assistance they have received not being counted as cost-sharing, and why do they have to come up with thousands of additional dollars to pay for their prescriptions. These people are desperate, wondering why the government is not enforcing the Court’s decision, and want to know what they can do and are willing to hire lawyers to help them out.

Below are just a couple of these real-life patient stories we received this year:

South Carolina Family, Husband w/Stage 4 Colon Cancer:

We are currently in the awful situation where we had a co-pay coupon/assistance from a drug manufacturer to help relieve the burden for our medical bills for a drug which has no generic option.

My husband is fighting stage 4 colon cancer, and has been for 6 years and counting. You can imagine the burden of year after year deductibles having to be met. So, when we came across what seemed to be a HUGE blessing from drug manufacturer Taiho for chemo drug Lonsurf in January 2024, we were soooo thankful! Only to be surprised SC BCBS did NOT apply this to our deductible. As best as I can tell, Lonsurf is still patent protected which means a generic version is NOT available. By my understanding of the ruling in late 2023, BCBS should be applying this to our deductible since there is no generic version available, but BCBS is NOT doing this.

I am not even sure you can help, but I’m just a wife/mom/caregiver trying to get some relief for my family. My husband is only 46 and my son is 7, and this deductible relief means so much to us as we battle this awful disease holding on to any time we have left as a family. It’s just so appalling the insurance companies would take this away from people in a fight for their life!

Crohn’s Disease Patient:

My husband has been prescribed Stelara, which does not have a generic equivalent, to treat severe Crohn’s disease. In January of this year we used a copay assistance card to fill the first dose for the year. Optum pharmacy was paid by the manufacturer the cost of our out of pocket maximum. However, they reported to United Healthcare only the $5.00 payment that we made. We were unaware that UHC was using a copay accumulator which makes us still responsible for the over $5,000 out of pocket max on our insurance. We have appealed to the 2nd level of UHC stating the federal findings regarding drugs that do not have a generic form. We just received the 2nd denial.

Couple, Both Living with HIV:

I wanted to follow up with both of you and let you know that both [NAME REDACTED] and I are falling under the situation where we each have had our copay cards drained for 2024, and now both insurance companies are coming after us for the full deductible amounts ($1750 for mine, $3000 for [NAME REDACTED]).

I sincerely hope that the HHS comes out with updated guidelines that firmly state, once and for all, that copay assistance must apply to deductibles.

Person Living with HIV

I’m on the last two weeks of my 90-day HIV meds, and for an additional 30 days, CVS is looking to bill me nearly $4,200. I do not have enough money for more HIV meds, and at this point in time, I had anticipated my Gilead co-pay coupon to fully cover my deductible and, in turn, cover my meds. My insurer, United Healthcare, continues to say they will not apply my co-pay coupon toward my deductible. Now, I’m unsure how to proceed.

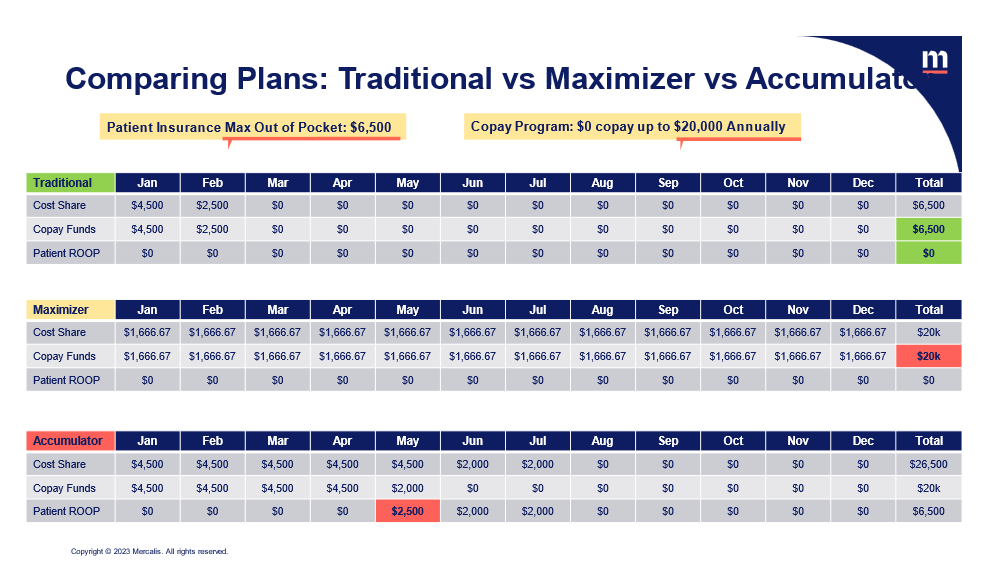

Patient Scenarios: Copay Accumulators and Maximizers

There has been some confusion, perpetuated by the payer community, as to the patient, drug manufacturer, and payer impact of copay accumulators and maximizers. Payers have repeatedly contended, even to the Court, that they do not collect the copay assistance and are not double billing and collecting more than they should under the ACA. While they are correct that they do not collect the copay assistance but rather the pharmacy does, they fail to mention what the pharmacy does with the copay assistance after they receive it. It flows back to the payers.

If it did not flow back to the payers, why would they be implementing copay accumulator programs and why are they defending them and working so hard to make sure the copay assistance does not count? It is clear that they are doing this to increase their revenues and profits, and at a great expense to patients. We are extremely disappointed that the federal agencies continue to take the side of the insurers and PBMs to the detriment of patients who depend on copay assistance to afford their medications.

As clearly described in the patient scenarios below, the patient pays much more in cost-sharing under the copay accumulator scenario compared to a patient whose copay assistance counts. Also, for both accumulators and maximizers the payers collect much more money than they should under the ACA when copay assistance counts.

Proliferation of Copay Accumulators & Copay Maximizers

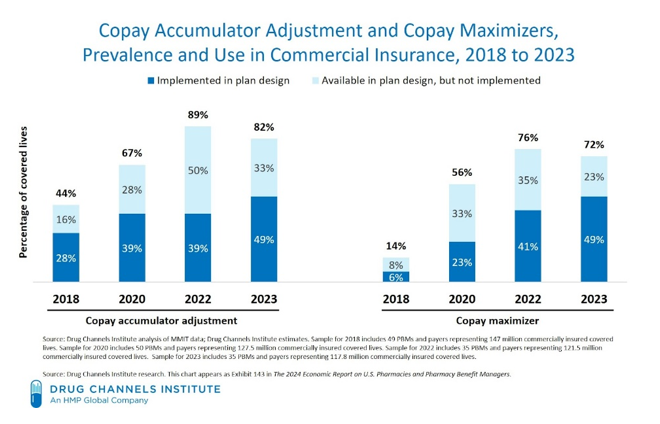

The use of copay accumulators and copay maximizer programs will continue to increase, due to the federal government’s inaction in issuing rules to stop them and their lack of enforcement of our favorable Court decision.

As illustrated in the graph below, in 2023, 49 percent of commercial plans had implemented copay accumulators. This compares to 39 percent in 2022. For copay maximizers, 49 percent of commercial plans had implemented copay maximizers in 2023, compared to 41 percent in 2022.

According to IQVIA, copay accumulator and maximizer programs accounted for $4.8 billion of copay assistance in 2023, more than double the amount attributed to these programs in 2019.[1]

Increased Out-of-Pocket Expenses for Patients & Their Impact

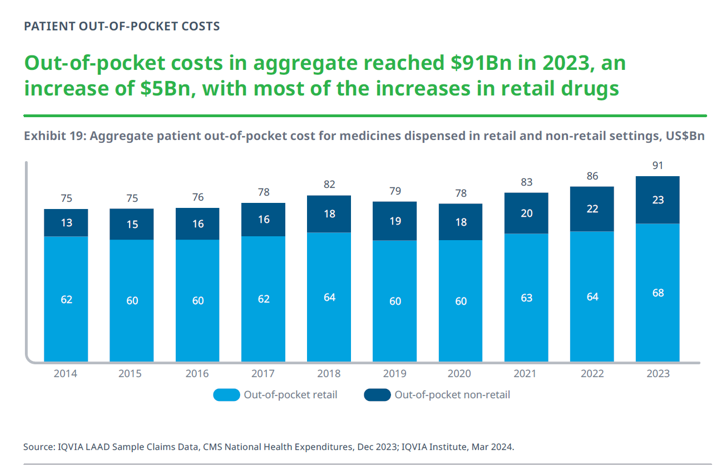

There is no doubt that patients need copay assistance in order to afford their prescription drugs, particularly due to high deductibles and high cost-sharing, often expressed in term of co-insurance based on the list price of a drug.

While there has been much attention to the list price of medications, patient out-of-pocket costs—the amount of money people actually pay for their drugs—are set by the insurers. Due to insurance benefit design, as described below, issuers are forcing beneficiaries to pay high costs, especially when compared to other healthcare services.

CMS has already announced that the maximum annual out-of-pocket cost will be increasing in 2026 by 10.3 percent from 2025. For an individual it will be $10,150 and for a family $20,300. The 2025 limits are $9,200 and $18,400, respectively. This is a great deal of money, which most people do not have, and it is on top of the cost of monthly premiums.

Due to the proliferation of high deductible plans, depending on the drug, an individual may be required to pay the total amount of $10,150 all at once for their medication at the beginning of the year.

According to CMS, the 2025 silver plan median deductible will be $4,928 while the bronze plan median deductible will be $7,323.[2]

That is why patients who rely on prescription medications rely on copay assistance. As illustrated in the graph below, according to IQVIA, in 2023 patient out-of-pocket costs for medicines in 2023 were $91 billion. That was an increase of $5 billion from 2022.

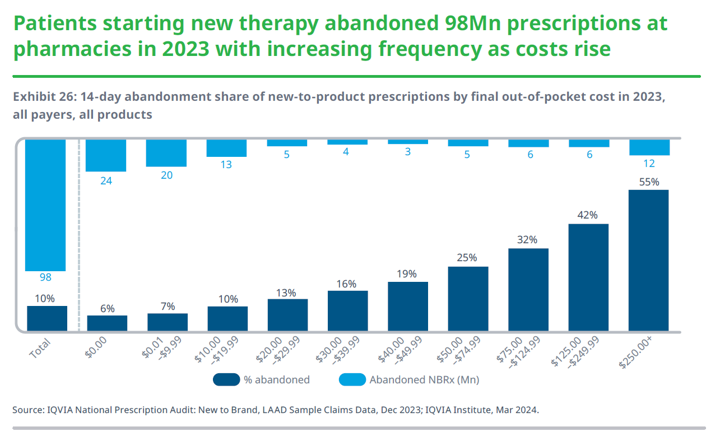

Due in part to high patient out-pocket costs, patients do not always pick up their prescription drugs. As detailed below, according to an IQVIA analysis, an estimated 98 million prescriptions were abandoned at the pharmacy in 2023 (compared to 92 million in 2022), with an abandonment rate of one in three for prescriptions with out-of-pocket costs above $75. For prescriptions with a final out-of-pocket cost above $250, 55 percent are not picked up by patients, as compared with 7 percent of patients who do not fill when the cost to them is less than $10.

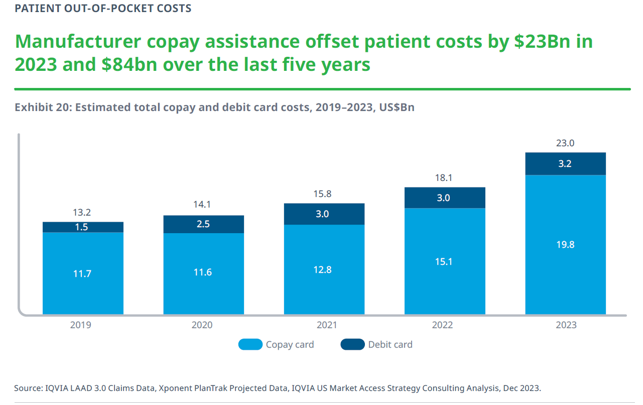

In order to afford their prescription medications, patients and families rely on copay assistance. In 2023, manufacturer copay assistance brought down patient costs by nearly $23 billion and accounted for 25 percent of out-of-pocket costs. Over the last five years, copay assistance accounted for $84 billion. Without copay assistance, the American people would have had to come up with all this money, which most people do not have.

Consider some of the other following studies and surveys regarding patient affordability of prescription drugs:

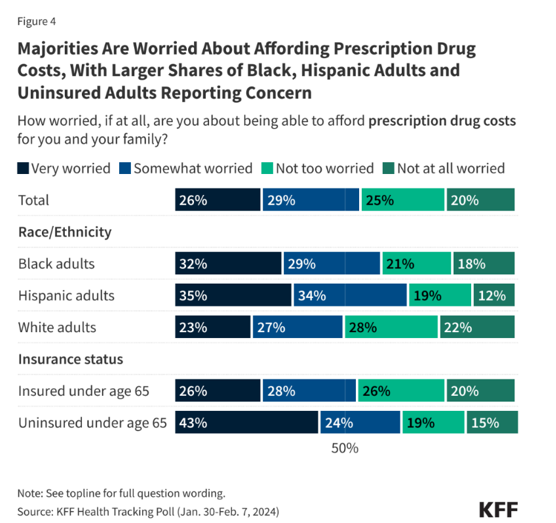

- In October 2024, KFF released a survey titled Public Opinion on Prescription Drugs and Their Prices.[3] According to the survey,

“over half (55%) of adults are worried about being able to afford their family’s prescription drug costs, including a quarter (26%) who are “very” worried. Larger shares of Black and Hispanic adults report being worried about affording prescription drug costs (61% and 69% respectively) compared with White adults, half of whom report being worried. A somewhat larger share of adults under the age of 65 without insurance (67%) report being worried about affording prescription drug costs, but still more than half (54%) of those who have insurance say they worry about these costs.”

The survey also found “about three in ten adults report not taking their medicines as prescribed at some point in the past year because of the cost. This includes about one in five who say they have not filled a prescription (21%) or took an over-the counter drug instead (21%), and 12% who say they have cut pills in half or skipped a dose because of the cost.”

- According to the Commonwealth Fund 2023 Health Care Affordability Survey: Many insured adults said they or a family member had delayed or skipped needed health care or prescription drugs because they couldn’t afford it in the past 12 months: 29 percent of those with employer coverage and 37 percent covered by Marketplace or individual-market plans.

Insurance coverage didn’t prevent people from incurring medical debt. Thirty percent of adults with employer coverage were paying off debt from medical or dental care, as were 33 percent of those in Marketplace or individual-market plans.

Medical debt is leading many people to delay or avoid getting care or filling prescriptions: more than one-third (34 percent) of people with medical debt in employer plans while 39 percent in Marketplace or individual-market plans.[4]

- According to CMS’ 2023 National Health Expenditures report, while overall healthcare spending grew at 4.1 percent in 2022, the increase in out-of-pocket spending was substantially higher at 6.6 percent to $471.4 billion. For prescription drugs, out-of-pocket spending totaled $56.7 billion, or 14 percent of the total spending on prescription drugs. This represents an increase of 11.6 percent in 2022 after slower growth of 6.4 percent in 2021.

However, for hospital care, which accounts for over three times more of total spending than prescription drugs, patients were responsible for paying only 2.6 percent. Despite the much smaller total amount of spending for prescription drugs, the out-of-pocket spending for prescription drugs ($56.7 billion) was higher than all the out-of-pocket spending for hospitals ($35.1 billion).[5]

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the high cost of prescription drugs caused more than 9 million adults between the ages of 18 and 64 to not take their medications as instructed. Women were most likely to skip or delay taking prescribed drugs and 20 percent of people with disabilities rationed their medications because of cost.[6]

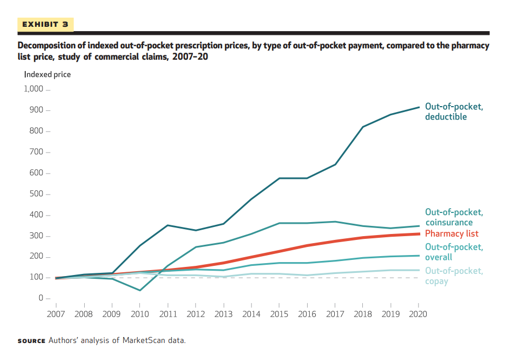

- An analysis of patient cost-sharing for prescription drugs in the commercial insurance market by staff of the Bureau of Economic Affairs found that between 2016 and 2020, out-of-pocket prices experienced faster growth than prices faced by insurers, after commercial rebates were accounted for. Through the period 2007–20, the authors found that “although retail pharmacy prices increased 9.1 percent annually, negotiated prices grew by a mere 4.3 percent, highlighting the importance of rebates in price measurement. Surprisingly, consumer out-of-pocket prices diverged from negotiated prices after 2016, growing 5.8 percent annually while negotiated prices remained flat.”[7]

Copay Accumulator State Bans Lead to Lower Patient Costs & Greater Adherence

A recent study (see Attachment 3) conducted by Oxford PharmaGenesis examined the impact of copay accumulator adjustment program (CAAP) bans in five states (Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Virginia, and West Virginia) and patient cost and adherence of autoimmune or multiple sclerosis drugs between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2021. The study found that “states that implemented a CAAP ban had relative reductions in patient liability after the first 2 months, which ranged from 41% to 63%, with monthly savings ranging from $128 to $520. Patients in states with a CAAP ban had 14% greater odds of being adherent to their treatment after policy implementation than patients in states without a CAAP ban and a 13% reduction in risk of discontinuing.”

Looking at patient liability, “in states without a CAAP ban increased from a range of $930 (January) to $88 (November) before the policy effective date to a range of $930 (January) to $103 (November) after the policy effective date. In contrast, in the states that implemented a CAAP ban, the mean monthly patient liability reduced from a range of $2,781 (January) to $303 (November) before the policy effective date to a range of $2,460 (January) to $164 (November) after the policy effective date. For states with a CAAP ban, relative reductions in patient liability were similar to those of states without a CAAP ban in January and February, whereas relative reductions were greater from March through December, ranging from 41% to 63% and monthly savings ranging from $128 to $520.[8]

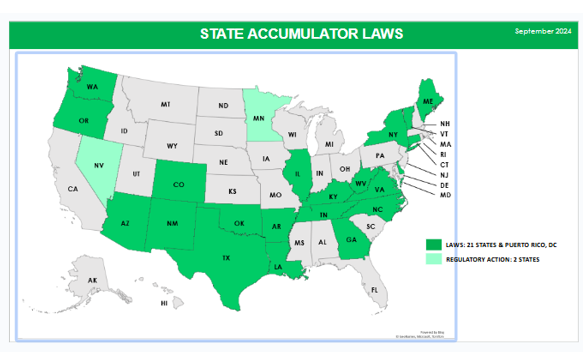

Confusion in the States

While the federal government is allowing insurers and PBMs to implement copay accumulators, 21 states, Puerto Rico, and DC have banned them legislatively for state regulated plans. Two additional states, Nevada and Minnesota, require, as they should, plans to abide by the federal Court decision. This patchwork is creating great confusion throughout the country for patients, regulators, payers, and drug manufacturers and is another reason why the federal government should issue a rule requiring copay assistance to count.

Covered Drugs Must be Included as Essential Health Benefits

The federal government is finally taking steps to clamp down on insurers and employers that abuse the Affordable Care Act by covering drugs without including them as part of essential health benefits. We are pleased that CMS did codify in the 2025 Notice of Payment and Parameters Rule the policy that prescription drugs covered in excess of the state’s benchmark plan are to be considered essential health benefits (EHB) in the small group and individual markets, and therefore, are subject to EHB protections, including annual cost-sharing limits. However, it did not make the same clarification for the large group and self-funded markets but said it would do so in the future.

Unfortunately, the 2026 Proposed Rule failed to include that important clarification. In order to close this loophole, we urge the federal agencies to issue a rule that applies this same principle to all plans.

Due to the federal government’s inaction, payers and vendors who use this scheme are able to continue to implement copay maximizers by exploiting copay assistance from drug manufacturers far in excess of the annual amount payers are entitled to.

In our comments on the proposed 2025 Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters Rule, we described how certain entities are working with employers and insurers to implement schemes that designate certain prescription drugs as “non-essential health benefits.” The drugs selected just happen to be the ones whose manufacturers offer copay assistance. The copay assistance does not accumulate toward the beneficiaries’ deductible or out-of-pocket maximum and the vendors then extract all the copay assistance for themselves and split it with the payers. To accomplish this, they force the beneficiaries to sign up for copay assistance programs but if they do not, require them to pay a high cost, such as 30 percent co-insurance.

As we wrote last year, it is rather ironic that while there are entities (including insurers) that voice strong opposition to copay assistance, at the same time they are working with others that are taking advantage of the copay assistance programs and extracting as much as they can for themselves.

To make matters worse, the federal government is allowing these schemes to continue and grow.

While stopping the use of “non-EHB” schemes will end the practice of copay maximizers, doing so without also requiring copay assistance to count will force patients from copay maximizers into copay accumulators. This is because maximizers drain copay assistance from drug manufacturers while they set the copay at the level of the copay assistance which allows patients to pick up their drug without cost (although it does not apply to their deductible or out-of-pocket costs). As described in the patient scenarios above, accumulators have a much greater financial impact on patients. Therefore, it is necessary for the federal government to end the “non-EHB” loophole and make copay assistance count.

Also, in our comments last year, the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute provided many examples of the employers using these “non-EHB” schemes. Since then, we have updated that research and as of August 2024, we have identified 128 employers and 25 issuers that utilize outside vendors that designate certain drugs as “non-EHB” to evade ACA cost-sharing requirements (see Attachment 4). The list includes thirty private sector employers including the Bank of America, Chevron, Citibank, Hilton, Target and United Airlines; nine states such as Connecticut, Kentucky, and New Mexico; thirteen counties; five cities; eleven school districts and teacher retirement plans; 44 universities including Brown, Columbia, Dartmouth, Duke, Harvard, Loyola, Penn State, Texas A&M, and the University of California; and eleven unions including the New York Teamsters and the Screen Actors Guild. Our research also identified 25 issuers exploiting the EHB loophole, most of them part of the Blue Cross Blue Shield network in such states as Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Minnesota.

We also provided, in Attachment 5, a sample list of the “non-EHB” drugs that the vendor SaveOnSP selected for Network Health in Wisconsin. We also noted the many drugs selected that treat HIV and hepatitis.

Alternative Funding Programs (AFPs)

In addition to entities that designate “non-EHB drugs” in order to extract manufacturer copay assistance to implement a copay maximizer, there are other vendors that also use “non-EHB drug” designations to implement alternative funding programs. In these programs, patients who use certain medications are directed to enroll in an alternative program, which is not insurance, in order to bypass ACA laws and regulations relative to patient cost-sharing limits and other patient protections. They then find alternative funding mechanisms to pay for the drugs. If the patient does not comply, they will be left paying the full cost of the drug.

In our comments on the 2025 proposed rule, we described in more detail some of these companies and how they work. We described that for alternative funding one vendor uses “manufacturer free programs, grants/charities, our International Mail Order Pharmacy partner, domestic wholesale pharmacy and occasionally a copay card.” Another vendor forces patients to sign up for drug manufacturers patient assistance programs, which are free drug programs meant for people who are uninsured.

There are a growing number of other vendors that are working with insurers, employers, and PBMs around the country.

According to Laura Huff, vice president of Gallagher Research and Insights, at a presentation at Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus 2024, 5 percent of employers are using alternative funding programs. Huff also reported that in 2023, 64 percent of employers were not familiar or have not looked into them, but in 2024, 30 percent did look into them, but did not adopt them. While 5 percent are using them now, 7 percent are planning to implement them in the next two years.[9]

The impact on patients is profound. In a recent study published in the Journal of Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy (see attachment 6) that sampled 227 patients who had to use AFPs, they found:

“Most patients (61% [136/223]) first heard of the AFP as part of their health benefit when trying to obtain their medication. Of 198 patients, 88% reported being stressed because of the medication coverage denial and the uncertainty of obtaining their medication. More than half of patients (54% [115/213]) reported being uncomfortable with the benefits manager from the AFP vendor. On average, patients reported waiting to receive their medication for 68.2 days (approximately 2 months); 24% (51/215) reported the wait for the medication worsened their condition and 64% (138/215) reported the wait led to stress and/or anxiety.”[10]

The federal government must investigate and prohibit these harmful schemes.

We thank you for the opportunity to share these comments and look forward to working with you as you seek to make healthcare more affordable and accessible for more Americans. Should you have any questions or comments, please feel free to contact me at cschmid@hivhep.org. Thank you very much.

Sincerely,

Carl E. Schmid II

Executive Director

Attachments (6)

[1] Source: IQVIA LAAD 3.0 claims data, IQVIA US Market Strategy Consulting Analysis, December 2023.

[2] “Plan Year 2025 Qualified Health Plan Choice and Premiums in HealthCare.gov Marketplaces,” CMS, October 25, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2025-qhp-premiums-choice-report.pdf, page 14.

[3] https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/public-opinion-on-prescription-drugs-and-their-prices/

[4] Sara R. Collins, Shreya Roy, Relebohile Masitha. “Paying for It: How Health Care Costs and Medical Debt Are Making Americans Sicker and Poorer,” Findings from the Commonwealth Fund 2023 Health Care Affordability Survey, October 26, 2023, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2023/oct/paying-for-it-costs-debt-americans-sicker-poorer-2023-affordability-survey?check_logged_in=1&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter_axiosvitals&stream=top.

[5] “National Health Expenditure Data,” CMS, last modified 12/13/23, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet#:~:text=NHE%20grew%204.1%25%20to%20%244.5,18%20percent%20of%20total%20NHE.

[6] Mykyta L, Cohen RA. Characteristics of adults aged 18–64 who did not take medication as prescribed to reduce costs: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2023;(470). doi:10.15620/cdc:127680.

[7] https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01344

[8] https://www.jmcp.org/doi/epdf/10.18553/jmcp.2024.30.9.909

[9] https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/use-of-copay-offset-programs-expected-to-rise-amcp-nexus-2024

[10] Wong, W.B., Yermilov, I., Dalglish, H., Bienvenu, L., James, J., Gibbs, S.N. (2024). A descriptive survey of patient experiences and access to specialty medicines with alternative funding programs. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 30(11), https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2024.30.11.1308.