Cost-sharing for prescription drugs; Comments on 2021 notice of benefit and payment parameters proposed rule

Secretary

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

200 Independence Avenue, S.W.

Washington, D.C., 20201

Dear Secretary Azar:

The HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, a national, non-profit organization whose mission is to promote quality and affordable healthcare for people living with or at risk of HIV, hepatitis, and other serious and chronic health conditions, is pleased to submit comments on the proposed Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2021 (NBPP) rule. Our comments pertain to the cost-sharing requirements proposed in section 156.130(h) Use of drug manufacturer coupons.

At a time when the American people are rightfully complaining about how much they pay for prescription drugs, HIV + Hep cannot understand why the administration is proposing to allow insurance plans to not count copay assistance towards beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs and deductibles. This proposal, if finalized, would be a major setback for patients as they seek to access prescription drugs and goes against President Trump’s promise to make prescription drugs more affordable. We urge you not to finalize such an anti-patient proposal.

This proposal is a complete reversal of the administration’s policy included in the 2020 Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters rule that required copay assistance to count for brand name drugs that do not have generic alternatives or when a beneficiary accesses a brand name drug that does have a generic equivalent through an exceptions or appeals process. We do not know exactly what transpired between now and then, but we do know that some large employers and insurers voiced strong disapproval of the policy decision. HIV + Hep trusts that for the benefit of patients who rely on costly prescription drugs, the administration will, at a minimum, revert to the 2020 policy. Ideally, we believe that copay assistance should count in all instances.

Patients Rely on Copay Assistance

Patients are finding it harder to afford their medications. insurers are designing health plans that require patients to shoulder higher deductibles and place more drugs on tiers with high coinsurance. In order to afford their medications, patients must rely on assistance from manufacturers.

For plan year 2021, CMS is proposing that the maximum out of pocket be $8,550 for an individual. Due to the proliferation of high deductible plans, depending on the drug, a patient may be required to pay that total amount of $8,550 all at once for their medication at the beginning of the year. Even if it were much less than that, patients still have trouble affording their medications.

While it would be beneficial to have first dollar coverage for prescription drugs and reasonable copays, issuers are moving in the opposite direction with higher deductibles and higher cost sharing. According to a study conducted by Ezra Golberstein examining National Health Expenditure Accounts data, in 2017 individuals were responsible for paying 14 percent of the total cost of prescription drugs. However, for hospital care, which accounts for nearly three and half times more total spending, patients were responsible for paying only 3 percent. For physician and clinical services, the next largest service category, patients paid 8.5 percent of the costs. This is one reason why people are complaining about how much they pay for their medications; insurers are requiring them to pay a high percent of the total costs.

According to the IQVIA National Prescription Audit, Formulary Impact Analyzer (January 2019), total out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs was $74 billion in 2018. Of that amount, drug coupons amounted to $13 billion. If the proposal included in the NBPP were to be finalized, insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) would be free to not count the value of the coupons and patients would be responsible for paying all these costs. At a time when the administration wants to lower how much patients pay for their drugs, this would have the exact opposite impact.

Plans should not be concerned with who pays the cost sharing requirements. They still collect the money, whether it is from the beneficiary or the manufacturer. We have heard criticism that coupons steer patients to higher priced drugs. For many patients with serious and chronic illnesses who rely on high cost drugs, there are no generics or low-cost alternatives. Further, providers prescribe the medications that their patients need and do not select them on the basis of the existence of coupons. For people living with HIV, hepatitis, and many other serious and chronic conditions, all the competing manufacturers offer coupons, so there is no steering to a particular drug.

Excluding Drug Coupons from Definition of Cost-sharing

In the NBPP, CMS is proposing to change the interpretation of the definition of cost sharing to exclude expenditures covered by drug manufacturer coupons. If this were to be finalized, issuers would not be required to count coupons towards the annual limitation on cost sharing. Basically, CMS is indicating that plans do not even have to implement copay accumulator programs and the coupons will not count anyhow, period. Manufacturers will have little reason to offer coupons. Patients will still be able to pick up their medications, if they can afford them, but the cost sharing assistance will not count towards cost sharing and the coupons will never help them meet their deductible or out-of-pocket maximum.

In describing the regulation that CMS is referencing to justify this proposal, CMS omits essential language. The current regulation reads: “Cost sharing means any expenditure required by or on behalf [emphasis added]of an enrollee with respect to essential health benefits” (45 CFR Section 155.20). Drug coupons fulfill beneficiary cost-sharing obligations on their behalf. HIV + Hep strongly urges CMS not to change this definition in the final NBPP rule.

Higher Cost Sharing Will Lead to Lack of Adherence

If the rule were to be finalized as proposed and insurers and PBMs were to not count copay assistance, patient costs would increase dramatically. This would lead to greater nonadherence to medications and ultimately impact the life and health of patients. Patients already complain about their drug costs, which cause them not to pick up their prescriptions. According IQVIA National Prescription Audit, Formulary Impact Analyzer (January 2019), in an analysis of new starts of branded drugs, if patient out-of-pocket costs totaled between $50 and $74.99 per month, 30 percent of the patients would not pick up their medications.

If that amount was increased to $250 or more, over 70 percent of patients would not pick up their drugs. In another study by IQVIA, “Patient Affordability Part Two: Implications for Patient Behavior & Therapy Consumption” that examined which phase of the benefit design did prescription drug abandonment occur, 17 percent were due to copays and 23 percent were in the coinsurance phase, while 41 percent were in the deductible phase. Clearly this demonstrates that high deductibles and high coinsurance are the top reasons why patients abandon their medications. Having copay assistance greatly decreases the chance of prescription abandonment. In that same study, IQVIA found that in 2017, 12 percent of patients abandoned their brand drugs included in their study, even if they had copay assistance. If there were no co-pay card support, the amount would increase to 31 percent.

Copay Accumulators Allow Insurers to “Double Dip”

Perhaps the most overlooked aspect of the “copay accumulator” debate is that not only do patients pay much more money for their prescription drugs, but the insurers collect more money. The insurer not only collects the value of the copay coupon, but then after it is maxed and the patient then has to pay the out-of-pocket costs, the insurer then collects all that money as well. Additionally, the drug manufactures end up paying more money. The only players that this policy is good for are the insurers and the PBMs.

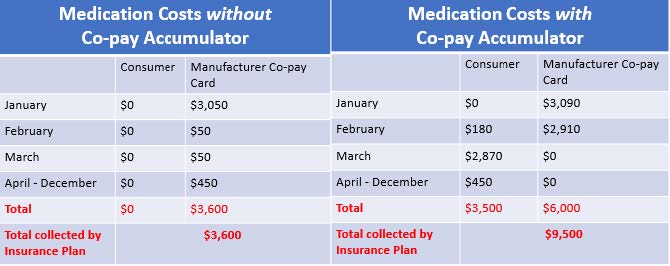

[Assumptions: Plan Deductible: $3,000; Drug Cost Sharing: $50, after deductible; WAC price for drug: $3,090; Plan out-of-pocket maximum: $6,000; Manufacturer copay assistance annual maximum: $6,000. Patient scenarios were developed by NASTAD and adopted by The AIDS Institute.] Above are two scenarios for a patient accessing a single tablet antiretroviral drug for the treatment of HIV. To the left is a patient in which copay assistance counts. To the right demonstrates how things change when copay assistance does not count. Under this scenario, the patient pays a total of $3,500 more over the course of one year, the drug manufacturer pays $2,400 more, and the plan receives $5,900 more by implementing a copay accumulator.

Need for Transparency Almost all plans that have implemented copay accumulator policies conceal them in plan contracts and leave patients unaware of the increase in patient costs. HIV + Hep is pleased that language is included in the preamble of the NBPP that CMS expects issuers to prominently include information on how they treat coupons on websites, brochures, and plan summary documents. HIV + Hep believes that exclusions to what plans consider as out-of-pocket costs must be included in the plan’s Summary of Benefits and Coverage document. HIV + Hep urges you to abandon this proposal. If it were to be finalized, it will be interpreted as a license for health plans to implement copay accumulators. It will increase patient cost sharing for prescription drugs, and the outcry over the cost of prescription drugs by the American people will just grow even louder. HIV + Hep thanks you for the opportunity to provide these comments. Should you have any questions, please feel free to contact me at cschmid@hivhep.org or (202) 462-3042.

Sincerely,

Carl E Schmid II

Executive Director

cc: Seema Verma, CMS Randy Pate, CCIIO Joe Grogan, The White House